Year-end wrap-up

Happy holidays! I wish you much creative inspiration in the coming year. I hope 2026 lets you spend time with the people you love and share things that bring you happiness.

Thanks for following my work and projects. If you're looking for a gift for a tech- or creatively-oriented person in your life this December (especially if they like video games or graphic novels), here are some options available from my website:

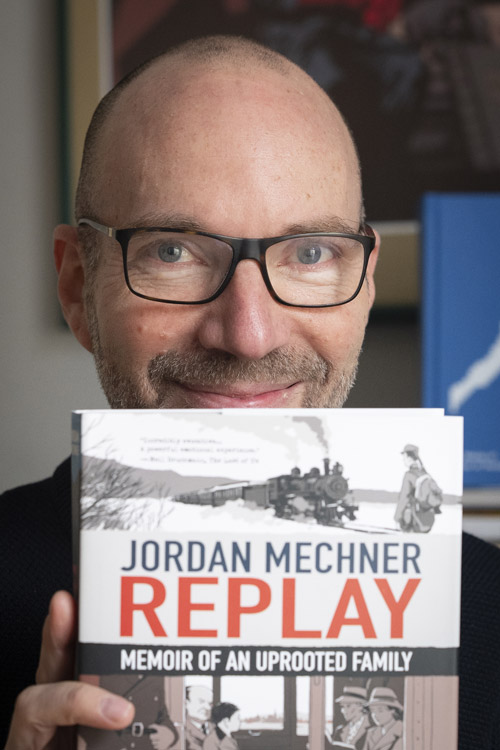

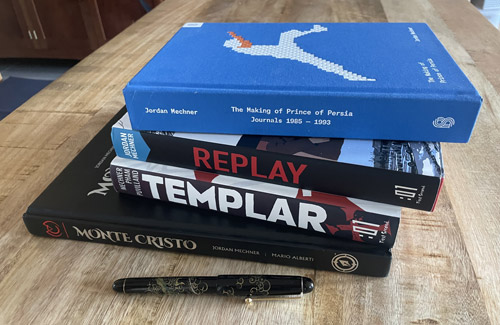

- My graphic memoir Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family, which interweaves video game creation with a multigenerational family story

- The Making of Prince of Persia, my 1980s game-dev journal (illustrated hardcover edition from Stripe Press)

- Monte Cristo, my graphic novel with Mario Alberti, now in hardcover English integral edition

- One of my recent signed, limited-edition artworks (perhaps especially, but not only, for fans of Prince of Persia, Apple II, or The Last Express)

You can see my full list of 2025 holiday offerings on the homepage, below the fold.

(For those in France, the French site offers some additional options.)

And in case we have similar tastes, here are a few tech/creative books not by me that I highly recommend:

- Scriptnotes by John August & Craig Mazin

- Enshittification by Cory Doctorow

- Muybridge by Guy Delisle

- Lucas Wars by Renaud Roche and Laurent Hopman (Episode II just released in French)

The last two are graphic novels about obsessively-driven film pioneers, wonderfully told and a delight to read.

Coming soon

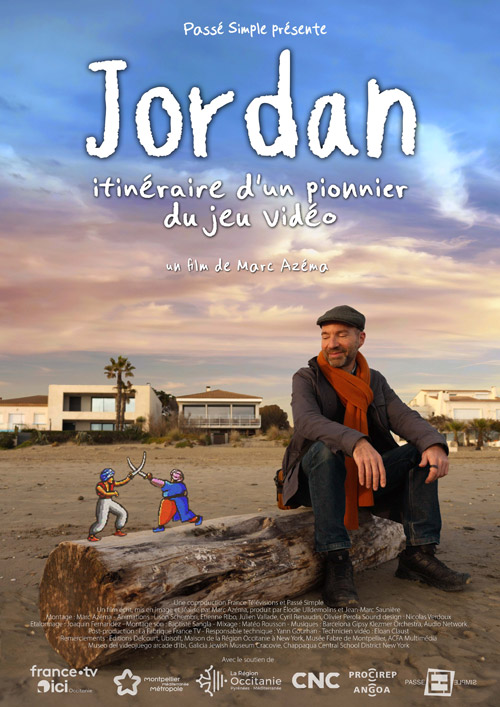

On Thursday, December 11, France Television will premiere "Jordan: A Videogame Pioneer's Journey," a documentary portrait by Marc Azema (in French). If you're busy that night (say, watching The Game Awards), France 3 will have Marc's excellent film on replay through January.

Exciting new announcements and releases are coming up in 2026. I'll post updates here and in the RSS feed. Enjoy December!