A platform-jumping prince

"Which is your favorite/definitive version of the original Prince of Persia game?"

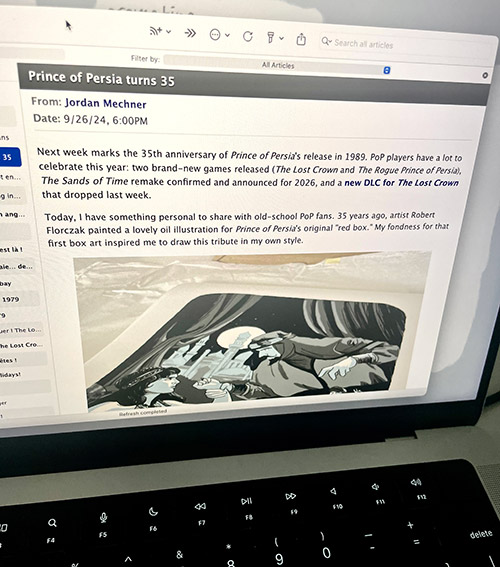

I get this question surprisingly often, considering it's been 35 years. I figured it deserves a blog post.

Apple II

The Apple II version was the original. It's the only version I programmed myself; Prince of Persia's gameplay, graphics, animation and music were all created on the Apple II. I spent three years sweating over every byte (from 1986 to 1989), so it's close to my heart in a way no other version can be. That said...

DOS/Windows

The 1990 PC version, developed in parallel with the Apple II and shipped a few months later, took advantage of the PC's improved graphics and sound capabilities to deliver the Prince of Persia most players remember (in CGA, EGA, or VGA). My dad, Francis Mechner, re-orchestrated his music (previously limited by the Apple II's tinny built-in speaker) for MIDI synthesizers. The Broderbund in-house team, led by programmer Lance Groody, with Leila Joslyn on art, Tom Rettig on sound, and me as director, stayed faithful to the Apple game while upping the quality in every dimension. The digitized spike and slicer sound effects that traumatized many an elementary-school gamer originated with the PC version. If someone asked me the best way to play old-school PoP online today, I'd likely recommend the DOS version.

In 1990, C-family programming languages were the future, 6502 machine language the past. For good reasons, nearly all subsequent ports of PoP took the PC version as their starting point, rather than the Apple II.

Amiga

The Amiga port was developed by Dan Gorlin (of Choplifter fame), in parallel with the PC version, using the graphics and sound assets developed by the Broderbund team.

Danny was one of my game-author heroes. Playing Choplifter, as a 17-year-old college freshman in 1982, blew me away and set me on the creative path that would lead to Karateka. I was star-struck that he agreed to port PoP to Amiga. He did an impeccable job, working alone at home, using the state-of-the-art development system he'd built for his games Airheart and Typhoon Thompson.

In a detail perhaps mainly interesting to lawyers, Amiga was one of three PoP versions (Apple II and Macintosh were the others) that I was contractually responsible for delivering to Broderbund, rather than their doing the development. This meant me driving to Danny's house for meetings instead of to Broderbund, and that I was on the hook in case the project fell behind schedule or something went wrong. Fortunately, with Danny, all was smooth sailing.

Commodore 64

One port that didn't get greenlit was the Commodore 64. Like the Apple II, the C64 had its heyday in the mid-1980s. By 1990, Broderbund (and most U.S. retailers) considered the C64 and Apple II outdated platforms; sales numbers were dwindling by the month. Broderbund couldn't escape publishing PoP on Apple, since it was the lead platform I created the game on, but they had little interest in a C64 version. It would have been a tough port in any case. To fit PoP into 64K of memory, with the Commodore's technical limitations, needed an ace 6502 programmer.

In a twist I'd never have predicted, an unofficial, fan-made C64 port was finally done in 2011, over 20 years later, and a Commodore Plus/4 port just last year. I hope my Apple II source code was helpful.

Macintosh

In 1984, Apple unveiled the Macintosh computer (with a now-legendary Super Bowl ad). Still in college, and flush with Karateka royalties, I took advantage of the student discount to purchase a 128K Mac — keeping my Apple IIe for games. (A computer with no lowercase, and enough RAM to hold four pages of text, isn't ideal for writing term papers.) I loved my Mac, and faithfully upgraded my system every time they did: Mac Plus, SE, II, IIci, LC. By 1990, I was proudly Mac-only.

But the games market was overwhelmingly PC. Broderbund estimated Mac's games market share as 5% of DOS/Windows. Since I believed in the Mac more than they did, it made sense for me to take on the port, as I'd done with Amiga. I subcontracted it to Presage Software, a group of ex-Broderbund programmers I'd known since Karateka days.

Fun fact: the previous occupant of Presage's San Rafael office was George Lucas's Industrial Light & Magic.

Presage had an excellent, seasoned lead Mac programmer in Scott Shumway; but whereas Danny met his Amiga milestones promptly, Scott's Mac milestones receded like the horizon as they approached. With each new Mac model release — black-and-white, then color, then a different-sized screen — Presage had to redo the bit-mapped PoP graphics for the new configuration. While Prince of Persia's Apple, Amiga and PC versions languished on store shelves (the game wasn't a hit in its first two years), the Mac release date slipped from 1990 to 1991, then to 1992.

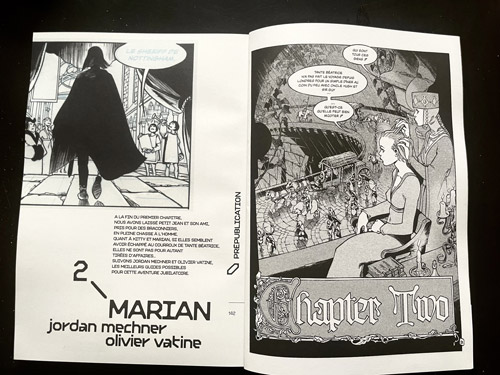

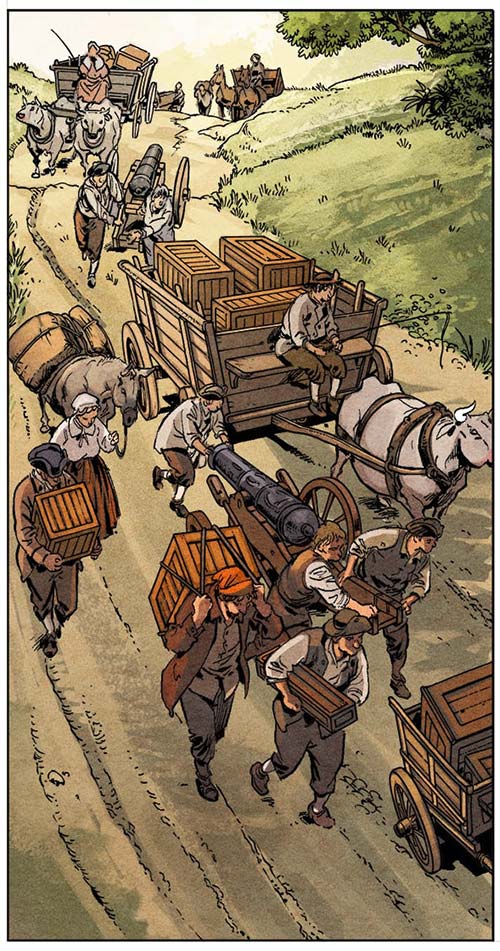

Fun fact #2: the young graphic artist who up-rezzed the Mac sprites, Mike Kennedy, went on to found the comics imprint Magnetic Press. We met again in 2024, when Magnetic published my graphic novel Monte Cristo.

Ironically, the Mac delays turned out to be a blessing in disguise. By the time the port was finally finished, almost two years late, Broderbund marketing had noticed that despite PoP's lackluster U.S. sales, its overseas and console versions were doing surprisingly well. Maybe the game had untapped potential?

Broderbund took the gamble of combining PoP's Mac release with a PC re-release in a bigger, hourglass-shaped "candy box" designed by the San Francisco firm Wong & Yeo. The dual Mac-PC release in the new box turned the prince's fortunes around. PoP not only became the #1-selling Mac game, it went from ice-cold to hot on PC as well. To 1992 Mac owners who'd been using their machines mainly for work, a game like PoP was a welcome diversion.

The Mac port was terrific. We adopted its revamped prince (sporting a vest, turban and shoes) for the sequel, Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow and The Flame. The high-resolution sprites and new costume came from the excellent 1990 PC-9801 port developed by Arsys in Japan.

But I still think the original Apple and PC graphics play best. The CRT blur and fat pixels smoothed over animated glitches, enhancing the illusion of life. Higher resolution leaves less to the imagination. (The same can be said of photography and cinema.)

Other ports

Between 1990 and 1993, more computer and console ports of PoP than I can list — Nintendo NES, Game Boy, SEGA Game Gear, Genesis, Master System, Amstrad CPC, Atari ST, NEC PC-9801, FM Towns, Sam Coupé — were developed by teams in Japan, Europe, and elsewhere. Usually, by the time someone handed me a controller to playtest a build, it was too late for my feedback to matter, so I rarely played beyond the first level or two. I don't remember enough specifics of those versions to compare them; I'll leave that to players who know them better.

There is one unforgettable exception.

Super Nintendo

In March 1992, I moved to Paris for a year (to learn French and 16mm filmmaking). Soon after my arrival, a colleague at Activision invited me to visit their office. They showed me the Super Nintendo version of PoP, developed by Arsys and published by NCS in Japan. Activision was lobbying Broderbund for the rights to publish it in Europe and the U.S. It wasn't my call, but they hoped I'd put in a word.

I wrote in my journal that day:

"Wow! It was like a brand new game. For the first time I felt what it's really like to play Prince of Persia, when you're not the author and don't already know by rote what's lurking around every corner."

Arsys had done more than a straight port; they'd expanded the game from 12 levels to 20, adding new enemies, traps, setpieces, and new music. I didn't play all the way through — a half-hour in Activision's office only scratched the surface — but I'll never forget the delighted thrill of being surprised playing my own game. You can see and play it in your browser here.

Elaborate production values and doubled playtime helped make SNES PoP a huge hit. I especially loved the fantastic box artwork by Katsuya Terada.

A recent feature article in Time Extension revealed behind-the-scenes details about the SNES development that I hadn't known — including that game producer Keiichi Onogi traveled to the U.S. to visit Broderbund in 1991, hoping to get my feedback. (I missed his visit.) The article is a fascinating time capsule and testament to how special that port was.

...And onwards

The SNES, so different from the original Apple/DOS version, gave me my first taste of a feeling I would grow used to in decades to come: playing and enjoying new Prince of Persia games that were made by others. With the exception of The Sands of Time (2003), where I was part of a Ubisoft Montreal team, the more recent modern PoP games don't have my fingerprints on them.

I suspect that for many reading this post, your answer to "Which is your favorite PoP?" will be the same as mine: Whichever version we played, for hours on end, at a formative age when playing and finishing a game mattered intensely. The real value is in the ingenuity and imagination you brought to the effort, and in your own memories tied to that time.

Thanks for reading this post. If you'd like a deeper dive into the story behind Prince of Persia's creation, I've published two books on the subject: my old journals (1985-1993), and my new graphic novel Replay. You can check them out here. Archival materials about PoP (including the Apple II source code) can be found in this website's Library.